Ahhhh, sake. I’ll be honest – I know next to nothing about the stuff, other than the fact that I need to get to know it better. That said, one sake I’ve really been blown away by every time I’ve had over the past few years has been the canned sake from Japanese brewer Kikusui (interesting how the craft-sake-in-cans thing in Japan parallels the craft-beer-in-cans thing here in the states). Their most commonly found version – the yellow can – is the base Kikusui Funaguchi Honjozo Nama-sake. It’s joined by a longer-aged and more “refined” version in red; plus a once-a-year, freshly-harvested version in green. They’re all pretty spectacular – with a common backbone of lush, floral, tropical fruit – but there are enough distinctions among the three to make a side by side tasting really interesting. If you’re lucky enough to come across a can(s), these Kikusuis are a great way to explore distinctive sake at a low tariff – they’re typically $6-$10 retail depending on the type, and each can (at 19% alcohol) makes a nice serving for two people.

Kikusui dates back to 1881 in the sake business – which makes them a youngster among Japan’s many historic sake brewers. The name Funaguchi is, as far as I can tell, a trademarked name meant to communicate “raw sake on tap”- reinforcing the fact that this is a nama-sake – unpasteurized. Honjozo is a term that specifies level of refinement – typically 30% of the rice polished away (whereas more refined ginjo has at least 40% polished away, and the daiginjo at least 50%). The fresh harvest green can gets the designation shinmai, and the red (aged one year) is actually a ginjo rather than a honjozo, but still a nama-sake. Got all that?

Kikusui dates back to 1881 in the sake business – which makes them a youngster among Japan’s many historic sake brewers. The name Funaguchi is, as far as I can tell, a trademarked name meant to communicate “raw sake on tap”- reinforcing the fact that this is a nama-sake – unpasteurized. Honjozo is a term that specifies level of refinement – typically 30% of the rice polished away (whereas more refined ginjo has at least 40% polished away, and the daiginjo at least 50%). The fresh harvest green can gets the designation shinmai, and the red (aged one year) is actually a ginjo rather than a honjozo, but still a nama-sake. Got all that?

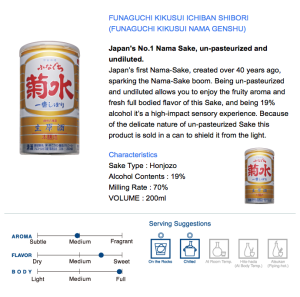

Actually, Kikusui has some good detail on their website that helps explain each of these three varieties. First, though, here’s what they have to say about what makes their sake special:

The KIKUSUI brewery is located in Shibata City towards the northern end of Niigata. One defining characteristic of this area is the abundance of groundwater sources carring the clear, pristine water from the melted snow. The snow that falls on the Iide mountain range, which rise over 2,000 meters above sea level becomes perfect soft water. One of the key ingredients for Sake brewing is water and here there is an abundance of pure soft water. We at KIKUSUI feel blessed to be in an area so ideally suited for Sake brewing.

Niigata Prefecture is one of Japan’s largest food producers. In particular, “Koshihikari”, a brand of premium rice grown in Niigata, has been Japan’s most popular brand of rice for many years. Each grain is round and plump and when cooked is sticky with a pleasant texture. It has a delicate sweetness and fragrance when freshly cooked and is well known for its pleasant flavor after it has cooled. The flavor of this rice, like Sake, stems from the abundance of pristine water from the mountain snowmelt.

Sounds good to me, and there’s no doubt that the water and rice Kikusui use come together to make a beautiful drink. Let’s start with yellow, which, according to Kikusui was “Japan’s first nama-sake over 40 years ago.” Like Kikusui’s notes say, the stuff is full bodied, lush in both taste and feel. There are notes of mango and papaya, and a general funkiness that hints at yeast and grain. Remarkable stuff. And at 19% alcohol (Kikusui calls it “un-diluted” as opposed to other sakes that typically clock in at 15%), this sake packs a punch. And, yes, be sure to serve it cold. I like it straight out of the can – which may be sacrilege, I have no idea – but it just feels right.

Sounds good to me, and there’s no doubt that the water and rice Kikusui use come together to make a beautiful drink. Let’s start with yellow, which, according to Kikusui was “Japan’s first nama-sake over 40 years ago.” Like Kikusui’s notes say, the stuff is full bodied, lush in both taste and feel. There are notes of mango and papaya, and a general funkiness that hints at yeast and grain. Remarkable stuff. And at 19% alcohol (Kikusui calls it “un-diluted” as opposed to other sakes that typically clock in at 15%), this sake packs a punch. And, yes, be sure to serve it cold. I like it straight out of the can – which may be sacrilege, I have no idea – but it just feels right.

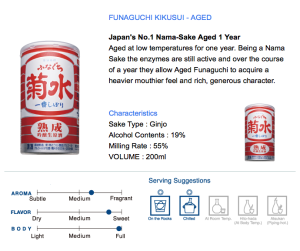

As for the aged version, in the distinctive red can, you can tell right away when you open this up that there is something different going on. The nose is both more smoothed out but also more intense, and when you taste it, you get a similar blend of smoothness and depth. The fruit is a bit darker – more plum than papaya – with a musky, honey undertone. The grain, too, comes through more strongly, more toasty. It’s hard to know exactly what the aging contributes vs. the more refined rice, and the family resemblance to the yellow can is unmistakable, but the aged version definitely kicks things up a notch.

As for the aged version, in the distinctive red can, you can tell right away when you open this up that there is something different going on. The nose is both more smoothed out but also more intense, and when you taste it, you get a similar blend of smoothness and depth. The fruit is a bit darker – more plum than papaya – with a musky, honey undertone. The grain, too, comes through more strongly, more toasty. It’s hard to know exactly what the aging contributes vs. the more refined rice, and the family resemblance to the yellow can is unmistakable, but the aged version definitely kicks things up a notch.

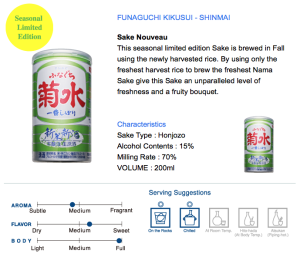

In the opposite direction, the shinmai “sake nouveau” (groan, did they actually just call it that?? kinda 1990’s, no?), also bears that family resemblance, though with more of a unique twist. It’s frankly a bit harsher at first, the alcohol less integrated. The fruit is crisper – think green apple and honeydew (is the green can subliminally putting those thoughts into my mind? I don’t think so… but maybe). You do get the grain and the yeast still, and the body is still full and fairly lush, but it’s more settled underneath the fresh, crisp fruit. The shinmai only comes out once a year, so it’s a bit harder to find. Here in Atlanta, it hit in spring, using the rice that was harvested last fall. Frankly, it’s my least favorite of the three given the more prominent alcohol notes, but it’s still a fascinating drink, especially side by side with the other Kikusui cans.

In the opposite direction, the shinmai “sake nouveau” (groan, did they actually just call it that?? kinda 1990’s, no?), also bears that family resemblance, though with more of a unique twist. It’s frankly a bit harsher at first, the alcohol less integrated. The fruit is crisper – think green apple and honeydew (is the green can subliminally putting those thoughts into my mind? I don’t think so… but maybe). You do get the grain and the yeast still, and the body is still full and fairly lush, but it’s more settled underneath the fresh, crisp fruit. The shinmai only comes out once a year, so it’s a bit harder to find. Here in Atlanta, it hit in spring, using the rice that was harvested last fall. Frankly, it’s my least favorite of the three given the more prominent alcohol notes, but it’s still a fascinating drink, especially side by side with the other Kikusui cans.

Luckily, Kikusui in general is not that hard to find. In Atlanta, I’ve found it at Hop City, Le Caveau, and Buford Highway Farmers Market, and it very well may be at several of the top liquor stores as well. Next time you see a can, pick one up – it’s sure to get you in the mood to learn more about sake.