There is something magical happening right now on the Atlanta restaurant scene. I’m not talking about the impressive numbers of new restaurants opening up on a seemingly weekly basis – though the numbers are indeed impressive. And I’m not talking about the big names coming to town – though names like Jonathan Waxman or Sean Brock are also noteworthy. I’m talking about restaurants that are bent on being bold. Being personal. Doing things differently. Crafting experiences with deeply human personalities that go beyond the surface-level sheen that so many of Atlanta’s restaurants of late have relied on.

So let’s pause now to celebrate the bold – those pioneers who may shape the very definition of restaurant dining in this city for years to come. Specifically, let’s celebrate three particular pioneering restaurants who are doing their thing in distinctly personal ways: the brand new Staplehouse, the barely open Ticonderoga Club, and tiny little Dish Dive, which opened just under a year ago. But before we dig in to why these three warrant celebration, it’s worth a quick detour to talk about how the stage was set for their arrival.

It’s clear that the past few years of economic growth in Atlanta has given restaurateurs a boost of confidence to go out on a limb. Krog Street Market and Ponce City Market both have been major engines driving restaurant openings, and neither would be here had the local economy (and the commercial real estate scene specifically) not ramped up significantly. In parallel, as the number of new restaurant openings goes up and up, the need to stand out and carve out a niche becomes more and more important. At this point, we’re all slightly, reluctantly, somewhat over the whole modern-Southern-local-farm-to-table-mania that seemed to guide every other new restaurant in Atlanta over much of the past decade. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Miller Union, Cakes & Ale, Empire State South, Restaurant Eugene, and their great forebear – Bacchanalia – are all restaurants that have brilliantly harnessed that mania and thrilled Atlanta diners in the process. But after a while, especially as the number of high profile restaurants in town increases, we simply need more diverse perspectives to have a well rounded dining scene.

Getting back to the embrace of the bold and personal that’s now happening, you could point to One Eared Stag as a precursor, with its ever-quirky personality and fearless combinations of flavors that can’t be disassociated from chef Robert Phalen. Or the completely unique, late-night-only, industry-centric Octopus Bar in EAV. Or Zach and Cristina Meloy’s Better Half, which is among the more prominent chef-driven supper clubs to have made the move to a full-scale restaurant, yet still maintains the personal touch of its supper club incarnation. If I had to pinpoint one single restaurant, though, that signaled to Atlanta that it was OK to go bold, it would be the aptly named Gunshow.

With Gunshow, open since 2013, Chef Kevin Gillespie and his crew took an intentionally polarizing stance on the dining experience – in a way that was meant to better connect the kitchen (the chefs) to the dining table (the patrons). One by one, the chefs cart out their creations to the dining room, explaining the dish, serving it up when they get the nod. This is not traditional dining, and, with its bare bones environment and totally unique pacing and delivery, Gunshow admittedly pisses some people off. And it also thrills a lot of people who are looking for a meal that gleefully messes with expectations (and delivers some stellar, intriguing food packed with personality in the process). And Gunshow is smart enough to know that it’s OK to piss some people off as long as you’re deeply connecting with others. Something is clearly working, as Gunshow remains one of the hardest-to-get reservations in town.

Which brings us back to three newer restaurants that, like Gunshow, are proudly waving their own particular brand of freak flag. The first of the bunch, Dish Dive, made its mark by being unrelentingly small and personal. Dish Dive equals chef Travis Carroll in the kitchen and Jeff Myers manning the house. 16 seats inside. BYOB. A super-concise menu. And you can’t help but feel that it’s Travis and Jeff’s (figural) house you’re dining in. It doesn’t get much more personal than that.To borrow a popular expression, Dish Dive gives no f*cks about what a restaurant is supposed to be. They know what they are supposed to be, and who they are trying to delight, and they do it with aplomb.

Meanwhile, newcomer Staplehouse furthers this idea of boldly building the restaurant-diner relationship in a few notable ways. First, they are a restaurant in service of a non-profit – the Giving Kitchen. And, while not the first restaurant to have a social mission as its underpinning, Staplehouse is certainly the most high profile. This gives them a built-in aura of true goodwill that – for those informed diners who are in on the aura – inevitably shapes the experience of dining there. You know you are supporting a cause with each ticket you purchase (more on that in a bit) and every bite you take. Even more, you know you are supporting the people who are most invested in that cause with each ticket you purchase and every bite you take. If you’re familiar at all with Staplehouse’s story, you know that the restaurant’s story is also the story of Jen, of Kara, of chef Ryan Smith. You could even say Staplehouse’s story is that of the entire Atlanta restaurant community in all its tragedy and triumph. This is a story, a dining experience, that people want to invest in.

Point two on Staplehouse – did you notice that they are not taking reservations, but rather selling “tickets”? They’re the first restaurant in Atlanta to adopt the Tock ticketing system used by many of the country’s leading restaurants. You could argue that this is a business-minded step away from the personal trust inherent in the typical reservation approach, but really, this path of selling tickets just reinforces the commitment from the diner to the restaurant – when you buy that ticket, you have given them your cash, and you are in on the cause before you even step foot through the door.

Smartly, Staplehouse realized that the ticketed seats inside the restaurant couldn’t be the only way to engage with diners. They built an outdoor patio, with its own little kitchen, ready for all comers with a menu that’s more affordable than the glorious (but admittedly pricey) tasting menu inside… but every bit as creative. And Staplehouse consciously avoided giving this outdoor patio a standalone name and identity (think Holeman & Finch for Restaurant Eugene, or Star Provisions for Bacchanalia), but rather embraced that Staplehouse itself needed to have more than one way to connect with diners. Simply put, Staplehouse is approaching the mission to deepen the restaurant-diner relationship in new ways, and bridging the casual/fine dining divide in the process.

Now for what may be the boldest restaurant of the bunch… Ticonderoga Club. If you haven’t (yet) heard much about this new spot from Greg Best, Regan Smith, Paul Calvert, David Bies, and Bart Sasso, that was intentional on their part. Ticonderoga Club is the result of a long-simmering stew of hush hush ideas that started way back in September 2013 (if not earlier) when Best and Smith left their founding roles behind the bar and front of house, respectively, at Holeman & Finch. Roughly a year later, Best and Smith confirmed that they would join the party at Krog Street Market, but still the details were few, from the name (which wasn’t revealed until one week before the place actually opened in October), to the very type of bar/restaurant it was going to be. Finally, now that Ticonderoga Club is open (although still awaiting signature on a liquor license as of this writing), the months of mystery are starting to make sense… Best/Smith/Calvert/Bies/Sasso weren’t just creating a bar and restaurant, they were creating an entire mythology.

Mythology, you may ask? Let’s just say that the Ticonderoga Club crew’s attention to storytelling rivals that of Homer himself. And this is not storytelling for the heck of it… the mythology here is in service of forging a bond between an establishment and its patrons. In an extensive reveal published by the Bitter Southerner, titled The League of Extraordinary Hospitalitarians, we learn that the Ticonderoga Club is actually (nix that… mythically) the Atlanta chapter of a 249 year old organization. The mythology extends in a printed Ticonderoga Club Quarterly, packed with philosophy and silliness in equal measure. The Bitter Southerner’s Chuck Reece hit the nail on the head, though, with the raison d’être of this whole elaborate backstory – which is fostering a feeling of gleeful hospitality. That won’t come as any surprise to fans of Best, Smith, and Calvert, who are all known for their skills as hosts, conversationalists, and all-around-fine-folks.

Is Ticonderoga Club quirky as hell? You bet. But isn’t it nice to see folks go out on a limb and do something different, especially when, at the end of the day, you know that they’re doing something different on your behalf? Ticonderoga Club, Staplehouse, Dish Dive… they’re all pushing the hospitality envelope in their own clever, even magical, ways. They’re not the only intrepid trailblazers in town doing so, but their lead is one to take notice of and celebrate. If their bold steps lead to something great, we all win.

by Brad Kaplan, November 6, 2015

Luckily, I discovered an old bottle in my liquor cabinet that eliminated the need for Kahlua. It was a

Luckily, I discovered an old bottle in my liquor cabinet that eliminated the need for Kahlua. It was a

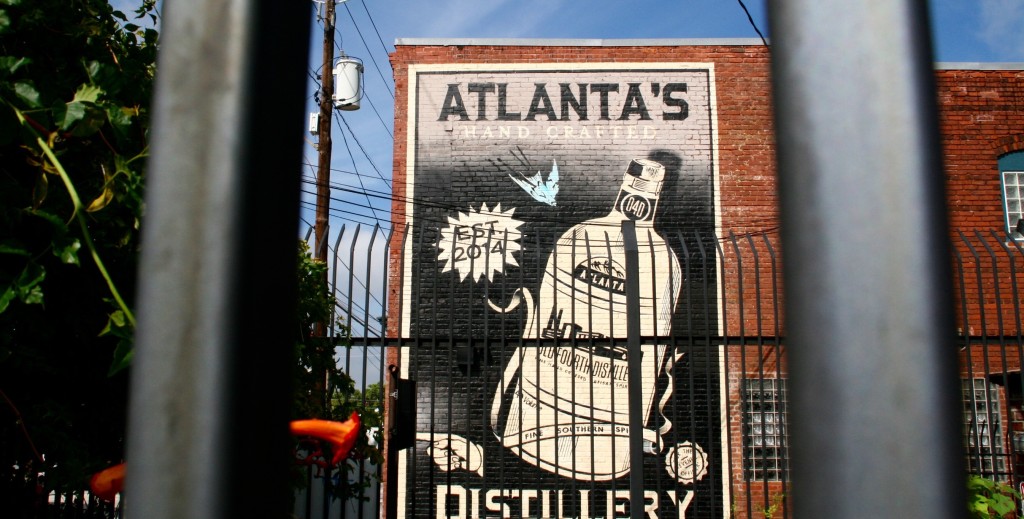

That said, many of today’s Georgia distilleries are indeed finding a way to succeed despite the challenging regulatory environment. Old Fourth Distillery is thriving in Atlanta, Richland Rum is now selling their heralded Georgia rum as far away as Europe and Australia, and there are a few micro-distilleries like Lazy Guy getting really creative with their offerings.

That said, many of today’s Georgia distilleries are indeed finding a way to succeed despite the challenging regulatory environment. Old Fourth Distillery is thriving in Atlanta, Richland Rum is now selling their heralded Georgia rum as far away as Europe and Australia, and there are a few micro-distilleries like Lazy Guy getting really creative with their offerings. ASW Distillery

ASW Distillery

Dawsonville Moonshine Distillery

Dawsonville Moonshine Distillery

Old Fourth Distillery

Old Fourth Distillery

The bead board on the walls, the marble on the counter, the wood in the tables – it’s all repurposed material steeped in Atlanta history, whether from the very same building O4D now sits in (the bead board), or from the gutted John B. Gordon Elementary School down the street that was built in 1909 (the marble). Jeff Moore told me, “We want to protect those kinds of things from being forgotten. It’s part of our story to be related to this area, this city.” Moore went on, and you could tell from his excited intonations that he digs into the minutia when it comes to rooting out the history of his building and the neighborhood:

The bead board on the walls, the marble on the counter, the wood in the tables – it’s all repurposed material steeped in Atlanta history, whether from the very same building O4D now sits in (the bead board), or from the gutted John B. Gordon Elementary School down the street that was built in 1909 (the marble). Jeff Moore told me, “We want to protect those kinds of things from being forgotten. It’s part of our story to be related to this area, this city.” Moore went on, and you could tell from his excited intonations that he digs into the minutia when it comes to rooting out the history of his building and the neighborhood: The marble (on the table), that was once dividers in the boys’ stalls in the school, you can see wher the toilet paper holders were. This is actually the same exact marble that was used in the Lincoln Memorial – from Tate, Georgia! We clad the walls with bead board that’s a hundred years old from this building, but also made displays with extra board that went out to liquor stores… and to now have that sitting in stores around Atlanta is very cool. We also used it inside out on the tables – you can see the stamp of Brooks Scanlon Lumber Company… if you’re a railroad guy, you know Brooks Scanlon… and you’d never find that until you pulled it off of our ceilings and looked at the back, and there it is. There are so many interesting stories like that. The seats are old church pews from nearby. It was unbelievably fortuitious how all these things came together – we didn’t have a design firm, we just let the materials we came upon help shape the space.

The marble (on the table), that was once dividers in the boys’ stalls in the school, you can see wher the toilet paper holders were. This is actually the same exact marble that was used in the Lincoln Memorial – from Tate, Georgia! We clad the walls with bead board that’s a hundred years old from this building, but also made displays with extra board that went out to liquor stores… and to now have that sitting in stores around Atlanta is very cool. We also used it inside out on the tables – you can see the stamp of Brooks Scanlon Lumber Company… if you’re a railroad guy, you know Brooks Scanlon… and you’d never find that until you pulled it off of our ceilings and looked at the back, and there it is. There are so many interesting stories like that. The seats are old church pews from nearby. It was unbelievably fortuitious how all these things came together – we didn’t have a design firm, we just let the materials we came upon help shape the space.

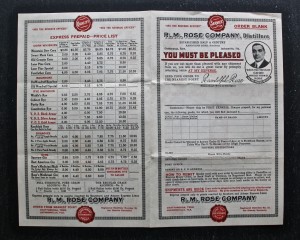

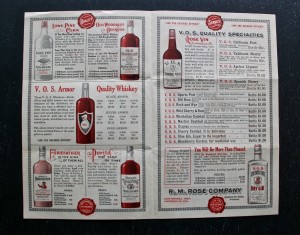

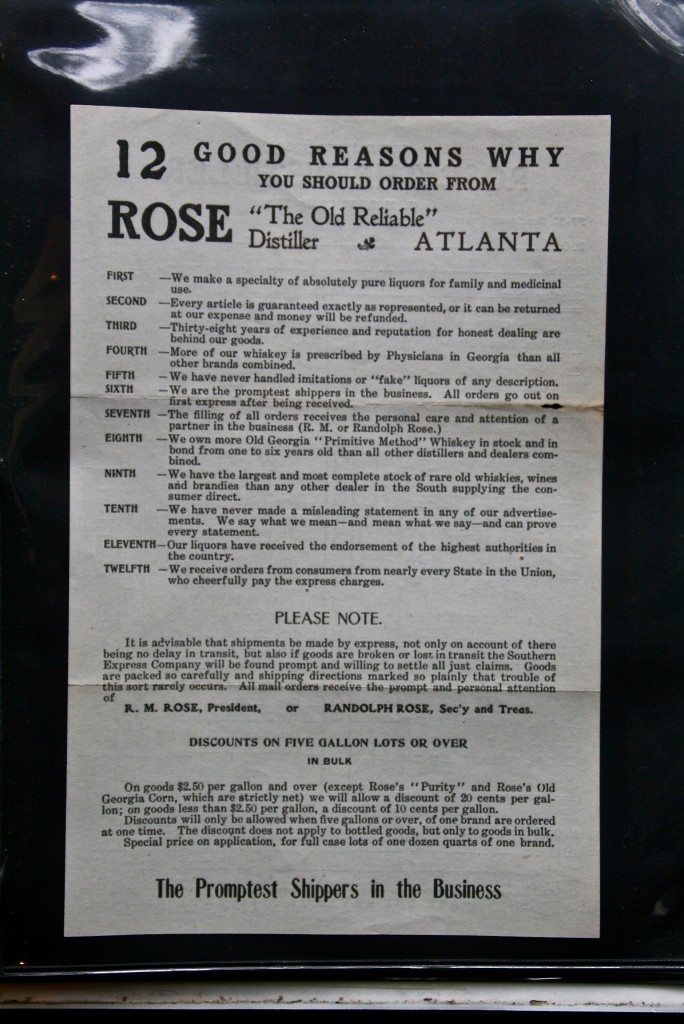

Their manufacturing was in Vinings, with offices and a retail store on Broad Street, and his big warehouse was on Auburn Ave. Around 1907, R.M. Rose was forced out of Atlanta, and moved first to Jacksonville, Florida, and later to Chattanooga. (At that time) it was not illegal (for consumers) to purchase spirits from Atlanta, so they would send R.M. Rose a money order and Rose would put a jug on a train for them (the consumer) to pick up. And 1907 to 1917 was their most prolific time period to advertise to make sure Atlanta knew he wasn’t completely gone. Right around 1917, the kibosh was put on that completely and R.M. Rose soon filed for bankruptcy.

Their manufacturing was in Vinings, with offices and a retail store on Broad Street, and his big warehouse was on Auburn Ave. Around 1907, R.M. Rose was forced out of Atlanta, and moved first to Jacksonville, Florida, and later to Chattanooga. (At that time) it was not illegal (for consumers) to purchase spirits from Atlanta, so they would send R.M. Rose a money order and Rose would put a jug on a train for them (the consumer) to pick up. And 1907 to 1917 was their most prolific time period to advertise to make sure Atlanta knew he wasn’t completely gone. Right around 1917, the kibosh was put on that completely and R.M. Rose soon filed for bankruptcy.